Computational Psychiatry¶

This page is a summary of what I’ve learned about computational psychiatry by reading a few papers by Quentin Huys and his collaborators. The goal is not to cover the details of the methodology, but rather to get a big picture of what computational psychiatry investigates and what the investigation process looks like.

Computational neuroscience (or sometimes theoretical neuroscience), as I understand it, is concerned with conjecturing and testing mathematical/algorithmic models of natural intelligence. Computational psychiatry uses the methodology of computational neuroscience to study how intelligent agents can go “wrong.”

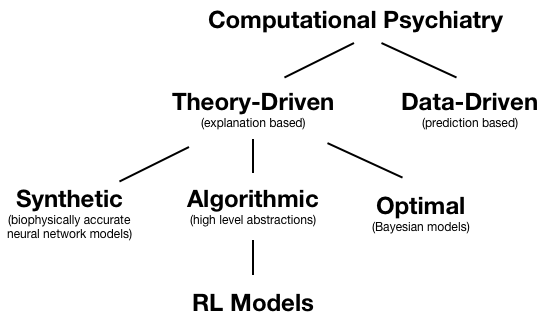

The methodologies employed by computational psychiatry (CP) are diagrammed below. [1]

We’ll be talking about RL models, which are algorithmic models. Within computational psychiatry, RL models typically consist of two parts: (1) an RL algorithm capturing internal learning and evaluation and (2) a link function which links internal evaluation to actions. RL models in computational psychiatry also typically have a small number of parameters that are neuroscientifically meaningful. These parameters are typically fit to experimental data. Hypotheses regarding these parameters can then be tested - for example, one can test whether dopamine antagonists reduce learning rate.

In particular, we’ll be talking about the paper Mapping anhedonia onto reinforcement learning: a behavioral meta-analysis. [2] I chose this paper because it seems to encapsulate the entire process: conjecturing models, fitting models, model selection, investigating the parameters of the model, and then relating it all back to neuroscience.

It’s been experimentally observed that for people subjectively reporting anhedonia, their behaviour is less effected by reward feedback. But we’re not sure why this is - is it because of (1) anhedonia, i.e. a reduced internal enjoyment of rewards, or (2) reduced dopamine levels, i.e. a reduced ability to learn from reward feedback. Note that in the paper, reason (1) is called a reduction in “primary sensitivity” to rewards.

The difference between primary sensitivity to rewards and ability to learn from rewards is made clear when we consider what they mean in a RL problem. Assume that we want to learn a Q-function \(Q(s,a)\) (which equals expected future reward given state \(s\) and action \(a\)). One way to learn such a Q-function is as follows:

In the above equations:

- \(\rho\) corresponds to primary sensitivity to reward

- \(\epsilon \in [ 0,1 ]\) corresponds to learning rate, i.e. ability to learn from reward. This is physiologically realised as dopamine (DA) signalling; it’s been found that \(DA \propto \delta_t\). I.e. the effect of dopamine is the control learning rate \(\epsilon\).

The question asked by the paper is if we can use the above Q-learning algorithm to figure out if the reduced behavioural effect of reward feedback in people reporting anhedonia is due to (1) reduced primary sensitivity or (2) a reduced ability to learn.

The experimental data was collected from a binary classification task given to humans from several groups (e.g. suffers from major depressive disorder, administered dopamine antagonist, etc.) The task was to classify a cartoon face as having a “short” or “long” mouth (the face is only shown for 600 ms total, and the mouth is shown for 100 ms). The twist is that the reward schedule is lopsided. Half of the participants are rewarded 75% of the time for correctly classifying long mouths and only 30% of the time for correctly classifying short mouths (vice versa for the other half of participants). The idea is that, in the face of uncertainty, participants should learn a bias for one of the actions.

The model used consists of the Q-learning model described above (the RL algo part) and several candidate link functions. All the candidate link functions take the following form:

In the above equations:

- \(p(a_t | s_t)\) is modelled as a logistic function where the score is based on the relative scores of action \(a_t\) and binary alternative \(a_t'\).

- \(W_t(a_t,s_t)\) is called “weights” in the paper, but I think a better label is simply score function. The higher the value of the function, the better the action being evaluated given current state \(s_t\).

- \(I(a_t, s_t)\) is called the “instruction” in the paper, it is simply an identity function on if \(a_t\) is the correct action given state \(s_t\) (evaluates to 1 if correct, 0 if wrong).

- \(\gamma\) corresponds to how much a subject cares about being right

- \(\xi Q_t(a_t, s_t) + (1-\xi)Q_t(a_t,s_t')\) corresponds to the expected value of the expected reward - we take an expectation since we’re uncertain if the observed current state \(s_t\) is truly the current state. Hence \(\xi\) corresponds to the probability confidence we assign to our observation of being in state \(s_t\).

Using the above framework, we can specify three candidate link functions:

- In the “Belief” model, \(\xi\) is fitted from the data.

- In the “Stimulus-Action” model, \(\xi = 1\), i.e. participants are assumed to be certain in their state observations.

- In the “Action” model, \(\xi = 0.5\), i.e. participants are totally uncertain about state observations.

In all the above candidate link functions, \(\gamma\) is fit from data. The full set of fitted parameters are \(\{ \gamma, \rho, \epsilon, Q_0 \}\) and additionally \(\xi\) for the “Belief” model.

The fitting methodology used is expectation maximisation (EM) I remember sitting in my ML class being very surprised when I learned that EM works - a note on EM is (hopefully) coming.

Model selection was done on the group level. We want to know which model best describes a group of participants (e.g. control group, anhedonia group, etc.) It was found that the “Belief” model best describes all groups studied. The model comparison technique used was Bayesian Model Comparison - a technique that balances fit and complexity by computing posterior proabilities for models. Unfortunately, I don’t know much more. The paper contains more details. This may be a topic for a future note.

The findings are that there is significant negative correlation between primary sensitivity \(\rho\) and measures of anhedonic depression (AD), and no significant correlation between learning rate \(\epsilon\) and AD. Additionally, it was found that administering a dopamine antagonist had the opposite effect - it reduced \(\epsilon\) but did nothing much to \(\rho\).

This means that anhedona affects decisionmaking primarily via reducing primary sensitivity \(\rho\) and not via learning rate \(\epsilon\) (related to dopamine). An obvious clinical application seems to be to decide against administering dopaminegernic treatments for depression. I’ll need to think about slash read into other clinical applications of this conclusion…

Some lingering questions, (which I suspect I can answer by delving into the methodology and experimental results):

- It seems that we can fit \(\rho\) via behavior due to the presence of \(I\) in the score function \(W\). But what justifies the presence of \(I\)? Why wasn’t a model considered with \(\gamma = 0\) - i.e. ignoring the \(I\) term. Also, can’t \(rho\) be more easily fitted if there was a no-action option with a fixed cost to taking action? Maybe the fixed cost would also be dulled…

If you found that interesting, other cool papers are A Formal Valuation Framework for Emotions and Their Control and The role of learning-related dopamine signals in addiction vulnerability. Also read the summarised papers for more detail.

| [1] | Computational psychiatry as a bridge from neuroscience to clinical applications |

| [2] | Mapping anhedonia onto reinforcement learning: a behavioural meta-analysis |